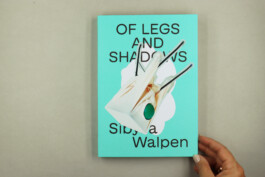

OF LEGS AND SHADOWS

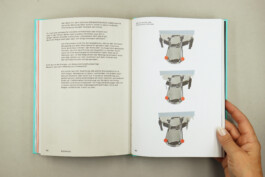

Wie kann man ein multidisziplinäres, unfolgsam herumstreunendes Werk zwischen zwei Buchdeckel pressen? Indem man alles Streunende und Gestreute einsammelt, ausbreitet und sich zu fragt, wo das Gemeinsame im Unterschiedlichen ist. Und indem man sich Partner sucht, den frischen Blick von aussen. In Zusammenarbeit mit dem Studio Bonsma & Reist entwickelte die Künstlerin Sibylla Walpen ein Werkbuch rund um die sechs Leitthemen #subjectobject, #cutfragment, #privatepublic, #holeconnect, #stillmove, #flatvolume.

OF LEGS AND SHADOWS lässt Arbeiten aus verschiedenen Entstehungszeiten und unterschiedlichen Kontexten aufeinandertreffen, macht mehrschichtige Bezüge sichtbar und regt zu neuen Lesearten an. Kurze Dialoge mit dem Autor Samuel Herzog umspielen und verorten die Leitthemen im gesamten Schaffen quer durch die künstlerischen Disziplinen.

Format: 240 x 170 mm, 216 Seiten, Softcover

Verlag: Edition Haus am Gern, Biel https://edition-hausamgern.ch

Grafik: Bonsma & Reist, Bern https://bonsmareist.com

Dialog mit Samuel Herzog, Zürich https://samuelherzog.net/

Druck: La Buona Stampa, Bellinzona https://www.labuonastampa.ch

Buchvernissage: AFF Space Bern, 29.8.2024 https://www.affspace.ch

Mit der freundlichen Unterstützung von

Culture Valais, Kultur Stadt Bern, Kultur Kanton Bern, Burgergemeinde Bern

DIALOG OF THE BOOK BETWEEN SAMUEL HERZOG AND SIBYLLA WALPEN

Samuel Herzog / Sibylla Walpen

#SUBJECTOBJECT

In his Aesthetic Theory, Theodor Adorno conjured up the moment when the portrait opens its eyes, when the artistic object suddenly becomes the looking subject. Do you think that, even in art, distinguishing between subject and object isn’t always easy?

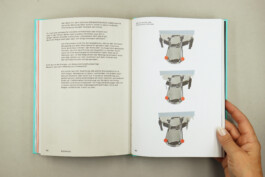

Yes, it’s not always easy for me to make a distinction in art either. Of course, as a maker, I’m a subject who creates a work, an object. But my work is always also about dissolving that boundary. I’m interested in creating something that leaves the status of an object and becomes a being or a subject: For GOBBO, the hunchback (p. 51), I took a projector frame, a shirt and three therapy balls and transformed them so that they were given a new identity and brought to life. GOBBO isn’t the image of a hunchback. Rather, it reflects the physical sensation of being stooped or hunched over. In this respect, the boundaries between subject and object become blurred.

Do they blur or are they overcome?

I’m interested in the symbiosis of subject and object, of man and thing. As a child, I had an inexplicable fascination with crutches. I was envious of my friend who had broken her leg while skiing and walked around with crutches for weeks. Sometimes I was allowed to borrow her crutches during the break: gripping the ergonomically shaped handle with my hand and feeling the cuff on my forearm gave me a completely new body sensation. I tried out new ways of moving, from swinging to galloping, as if I had three legs. When I later, as a student, saw Rebecca Horn’s ‘Body Extensions’ at an exhibition in Vienna, I was suddenly able to locate this affinity.

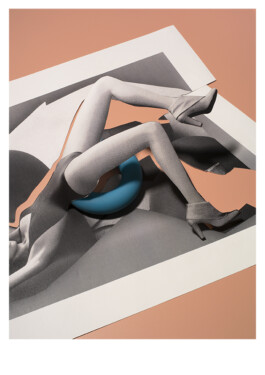

Shoes always play an important role in your work. Shoes are also objects that come to life when we wear them, and they become part of us - no matter how much they may have been objects in a shop window. Or is it the other way round? Do we become objects with certain shoes on our feet?

We can’t look at shoes without thinking about the person who wears them. Like no other item of clothing, they merge with the body to form a new whole, and, over time, they become a negative imprint of the feet. So, they take on more and more of the subject who wears them. But yes, you’re right: when I wear eye-catching shoes and the other person’s gaze quickly falls on them, it sometimes feels like I’m an extension of the shoes - and not the other way around.

Isn’t that a bit like in the play IT DEPENDS, for which you did the scenography? There, too, the perspectives are constantly changing, up becomes down - and subjects become objects …

Playing with the concept of upside down is something I’m interested in, because being upside down stimulates the brain to think and see things in a new way. Interestingly, today’s people recognition software generally does not recognise a person standing on their head because the head-on-top criterion isn’t met. In yoga, on the other hand, standing on your head is part of being human and it’s obviously important to stay balanced and not lose your grip on the ground.

In the production IT DEPENDS, the actors switch from an active role to a supporting role in the literal sense of the word: using strap-on plates, they become stage furniture - they transform themselves into objects instead of simply leaving the stage.

For example, one actor lifts a plate with outstretched legs, which turns into an office desk (p.73). Since the play is about multiple dependencies, playing with scenographic subject-object changes is also relevant in terms of content. It becomes unexpectedly funny when the objects, despite their passive role, interfere in the play from time to time, commenting on the action as ‘talking furniture’ or even divulging secrets.

#CUTFRAGMENT

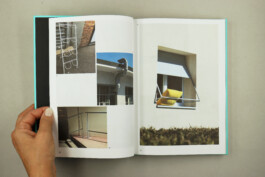

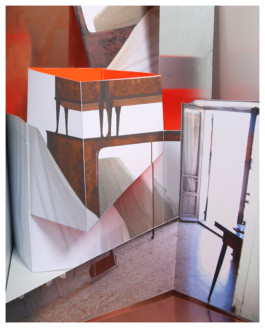

In your INTERMEZZI (pp.62–28), you show us very concrete elements of apartments (we recognise furniture, pictures, doors, walls), yet you never create the impression of a coherent space; everything always tilts out of coherence, tending towards flatness. What kind of game are you playing?

It’s an interlude, as the title suggests. The image fragments come from photos that I found on Italian real estate portals on the internet. There, houses in remote areas are offered for sale at low prices. We see deserted rooms, often still fully furnished, but already quite dusty. These pictures move me somehow, because they tell stories of past lives, but they also evoke ideas of a possible new life. It is this strange in-between state that interests me.

And how did this become a series of works?

For INTERMEZZI, I extracted fragments that I found interesting from a scenographic or narrative point of view and put them together to create new, fictional spaces. On the one hand, I wanted to create a concentrated solution, so to speak, that was either suggestive or interesting in terms of composition. On the other hand, I was also interested in playing with illusion: how many fragments does it take to suggest a space?

A not entirely coherent space, however.

That is true. But no less coherent than, say, Schwitters' Merzbau or the interiors of the Cubists.

Your approach to the fragment is different in relation to Art in Architecture. In HIE & DA (pp. 122–125), various human and animal body parts jut out of a wall; fragments that we automatically extend to whole bodies. In contrast to INTERMEZZI, where the spaces crumble under our gaze and become ungraspable, here our eyes fill in the missing parts. What were you interested in here?

When the Schadau Gymnasium high school in Thun was extended, artist Karl Geiser’s ‘Standing Boy’ was moved to another place. During my research, this figure put me on the trail of figurative sculptures in the school environment: boys, girls, fawns, kid goats … From the 1930s to the 1960s, many public buildings and parks were adorned with such sculptures. Today, some of these figures seem a little outdated, but they also somehow touch me. I tracked down such sculptures in the catchment area of the high school, scanned striking fragments with a mobile 3D scanner and finally reproduced them in plastic. The students, who come to the high school in Thun from far-flung regions, may recognise familiar shapes from their home environment, which are here regrouped and recontextualised in the same way as themselves.

In the case of twins, the question of the fragment arises in a particular way. Reading Erich Kästner’s novel ‘Das doppelte Lottchen’, one has the impression that two fragments (the twins separated by the separation of their parents) are reunited to form a whole. You designed a scenography for a theatre version of the story that suggests a slightly different reading of this situation.

Yes, in this version there is no intact world at the end. ‘Intact’, after all, means ‘whole’, ‘complete’. I took the twins’ separation very literally and dissected the stage elements: there were split walls, split beds, split tables. The cut surfaces were covered with neon red foil, which seals the ‘wounds’ but also emphasises them. There is no total reunification in this production. Instead, it shows an affirmative approach to the fragmentary: Even a separated family is still a family.

#PRIVATEPUBLIC

In the age of so-called social media, there’s much talk about the tense relationship between the private and the public. In your installation IN-TENSIONS (p.136–139) for Twingi Art 23, you took this relationship literally by looping neon lashing straps through the window openings and stretching them from window to window across the village square of Grengiols. These straps began to whisper in the wind, giving the impression that family secrets were being whispered from the old houses. The installation obviously evoked certain conflicts. Can you imagine why your installation irritated some of the residents?

I saw my intervention as a physical representation of the cohesion that’s needed in such a small village to create a future worth living: How do you counter the threat of emigration? How can the village centre be revitalised? What are people’s views on major projects in the pipeline? These are questions that concern and divide the population. I was aware that I couldn’t establish the desired connection without creating tension at the same time. Sometimes private concerns and sensitivities must be subordinated to the greater public interest. My installation physically connected residents with perhaps opposing political views via the tapes – and led the tapes into their private rooms. I underestimated how invasive this may have felt to some.

It’s astonishing when you think about how private things are put out there as a matter of course these days.

That’s true. But the village square creates a sense of identity and is clearly emotionally charged. Although most of the residents live in the suburbs in a very contemporary way, in the historic village centre they prefer things the way they’ve always been. My intervention confronted the residents – not entirely voluntarily – with contemporary installation art. It was to be expected that not everyone would like it.

Then there was the sound generated by the wind, which I hadn’t expected. It even robbed one resident of his sleep on some nights. The vibrating straps transformed the village square into the resonating chamber of a giant stringed instrument. Whispered family secrets? A beautiful idea! For me, the project has become a tribute to ‘d’Walpini’, my ancestors from Grengiols, even if it wasn’t intended from the outset. I like to imagine how these legendary musicians and dulcimer makers would have swayed to the deep vibrato or even played their own melodies.

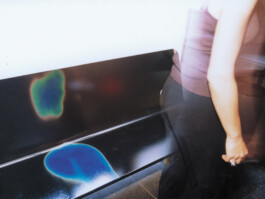

In 1995 you made the private sphere public in a completely different way with your MEMORY BANKS (pp.197–199). People left traces of their body heat on thermo-coated benches in the station concourse in Brig. Did that also cause irritation?

Yes, of course it did. But that’s exactly my point. Have you ever been on a bus and felt the body heat of the last passenger on the seat? There’s something uncomfortable about that, isn’t there? A stranger’s body heat in a public place can be disconcerting. In the MEMORY BANKS installation, the surface of the benches indicated the contact between person and object, visualising body heat as a temporary image. I was interested in the tension between the public space and the intimate private space that manifested itself there. Anyone who got up from the bench after sitting on it for a while and became aware of the marks left behind tended to react with some embarrassment. And indeed, the coloured stains on the benches were consistently avoided until the bench had cooled down and the image had faded away.

With the coronavirus pandemic that hit us a quarter of a century later, these marks suddenly took on a whole new dimension. Suddenly everyone saw blue everywhere, the world became one big MEMORY BANK …

#HOLECONNECT

A recurring motif in your work is the ring or the hole. Holes are very ambivalent. In everyday physical life, they are often ‘traffic routes’ for different things. Take our mouth, for example, a passageway for air and speech, but also for food, saliva or toothbrushes. In the field of language, however, holes almost always represent something that is missing: time holes, memory holes or absences that leave holes. For the project RING (pp.132–135) you pulled a huge metal ring through a mountain hole in the Twingi Gorge (VS). In CHEMISE (p.43), you used tubes to turn a shirt into a canal or cave system. And PLISSEE (p.41) or LOTTE/LOTTA (pp.56–57) also revolve around the hole, the tube, the canal. What interests you about the hole? Is it filled or empty for you?

The hole interests me as an opening that reveals something behind it. Or that connects one side to the other. The tunnel is a good example is. As a native of the Valais, I love the tunnels that quickly connect me to the north or south side of the Alps. Spontaneously, I would say that the hole is a framed nothingness, a blank space. And a ring can make a hole wherever you put it. But it immediately qualifies the void, because it at least frames air.

So, could one say that the hole in our atmosphere is always filled? Is that why you are so interested in this subject?

I like holes in my artistic work because, by looping through or penetrating them, I can create new connections and constellations and connect different things. In the Twingi Gorge, I pulled the object RING (pp.132–135) through the tunnel entrance and a side window so that it merged with the landscape. Unfortunately, the higher powers were not pleased with the connection and ordered a rockfall after a few weeks, and the object took some battering …

I also like dark holes. I like it when space narrows, when the light is swallowed up and the unknown opens up. In LOTTE/LOTTA (pp.56–57) you might ask yourself if a girl has been swallowed up; or is she even spat out?

For me, there’s no girl in LOTTE/LOTTA. The hair flows far too cleanly out of the funnel for that. For me, there’s nothing but nothingness in the container. And when I look at LOTTE/LOTTA, I feel that I’m being denied something. Whatever is in the container, it’s, how shall I put it, ‘impossible’? But perhaps the impossible is also a kind of hole?

I called the object LOTTE/LOTTA because it contains a hairpiece from the production ‘Das doppelte Lottchen’. And because ‘lotta’ means ‘fight’ in Italian and this production, which was very successful in the end, was accompanied by some ‘fights’ during the process. But struggles are simply part of the artistic process, because it’s always about wresting the possible from the impossible, a something from nothing.

So, after all, the impossible is a hole that’s filled in and therefore becomes possible?

What is the impossible for you? Do you mean the unimaginable? Because what I can’t imagine is impossible for me. But there are more things that are possible than I can imagine. LOTTE/LOTTA deliberately refuses to let us look inside. What you can’t see is at least as important as what you can see.

This dialectic also plays a central role in OTHERWORLD (pp.86–91), where a door is slammed back and forth between the obvious and the invisible.

Yes, I liked how the actors slipped through this swinging round flap like cats. The opening played a multifunctional role in the play; in one scene it was a door, later, tilted, it became a well hole. The independent theatre scene is often about finding flexible and therefore cost-effective solutions: The round hole was ideal because it could represent a wide variety of transitions.

In retrospect, I realised that the motif is not only obsessively repeated in the wallpaper, but also in the many Os in the text: OTHERWORLD or OTHERMOTHER … And I remembered that, according to my parents, as a small child - long before I could read - I liked to sit on their laps while they read the newspaper, looking for all the Os, pointing at them and saying ’OOOO’.

#STILLMOVE

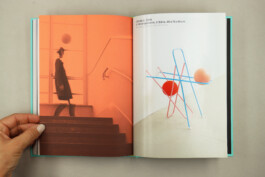

For the series TINY MOVINGS (pp.178, 183–185) you stuck fragments of newspaper pictures on the wall so that the wind would set them in motion, causing them to flutter back and forth. You then filmed these ‘animations’, turning ‘stills’ into ‘moves’. This is a very minimalist approach in which you leave a lot to chance and simply register how it works. What significance does chance have in your work?

Chance is too random for me. The world offers an infinite number of coincidences, almost all of which remain meaningless to us. I can only use those that seem meaningful to me at a particular moment in time, as in this case. During my time in Paris (2018), I cut out silhouettes from old Paris Match magazines and stuck them on the wall to use later for collages. There was a fan in my studio because it was sometimes over 40 degrees that summer. The cut-outs suddenly began to tremble and flutter in the wind from the propeller. I liked how these photographically frozen movements suddenly came back to life. So, I decided to continue working with video clips instead of collages.

The result looks effortless and has a certain naturalness to it.

Well, the production of such animations is very primitive on the one hand, but tricky when it comes to details: Where on the silhouette should I place the glue dots? Where should the movement take place? What’s the best direction of the ‘wind’ for optimal effect?

That sounds more like calculation than chance.

Chance, of course, also played a role. But I tried to influence the factors so that I could control the movement.

You also chose the motifs in such a way that, when animated, they tell little stories. I'm thinking of the officer, for example, who keeps tipping his hat.

I deliberately chose figures that gesticulate: officers shaking hands, two men holding open the door of an official car. The scenes are taken from contemporary political situations. Today, fifty years later, the gestures are empty; content and context are unknown to me. So, it was easy for me to decontextualise them: TINY MOVINGS does not tell of historical moments, but of public formalisms, and the loops deconstruct those patriarchal gestures. The man with the wardrobe (MENDONTGIVEUP, p.184) was part of an advertisement. But even he seems less heroic than ridiculous in his endless exertion.

You have a predilection for unstable conditions. This is also expressed in the tyres, balls or precarious frames that appear in some of your works. Are you interested in the power that lies in the possibility of things moving?

I’m interested in constellations that can become unbalanced or take on a new form at the slightest movement. The circle or the sphere are suitable forms for playing with the principle of equilibrium. Even if I create an assemblage so that it is temporarily still, the possibility of movement is present: the circle or ball stands very precariously on the floor. The slightest push and …

Is it about the energy that is inherent in contradictions, a dynamic comparable to nuclear fission?

I’m looking for the tension such constellations carry within them. Movement is latent, changes can be triggered physically or just in our imagination. This perhaps puts me at the other end of the traditional idea of sculpture as something stable and immovable. I like combinations that are in a dynamic balance, that aren’t fastened and fixed in a rigid way.

#FLATVOLUME

In many of your works, one can observe a play with the characteristic properties of the material. Things that protrude into the room, such as curtains, appear very flat. Conversely, shadows, for example, tend to assume a certain physicality. In the installation PURPLE CARPET (pp. 190–192), this takes on almost confusing forms: the frames, which are real and therefore also three-dimensional, appear almost two-dimensional, more like images of frames. What interests you about this play with volume and surface?

It’s interesting that in photography a prominent shadow is at least as effective as the object that casts it. Photography brings volumes and their shadows onto a common pictorial surface, making them much more equal than they are in spatial reality. I often bear this in mind when I move from two-dimensional to three-dimensional work: When I create spatial constellations, I also consider the shadows that the objects cast on the ground. I materialise possible shadows in order to bring the material and the immaterial onto the same level - just as in photography. This also gives the objects a solid base, an adherence to the wall or floor.

Are there any other characteristics of photography that you use in your work?

In PURPLE CARPET, the frames are spatial, but in their linearity, they look more like a drawing. Perhaps I am unconsciously trying to undermine the dichotomy of two- and three-dimensionality, perhaps it is about illusion and disillusion, about oscillating between fixed categories?

Another ‘dimensional change’ takes place when you look at a photograph of the installation. Have you also considered this transfer?

I’ve actually internalised the photographic view to such an extent that I find it difficult to see a spatial situation without its two-dimensional pictorial effect. And I’m not alone in this: in the age of Instagram, every situation is judged by its Instagrammability. For example, many interior designers now seem to focus primarily on what looks good in the photo rather than prioritising the real quality of the space.

The internet, which you often use as a source, adds a slightly different space, a new reality.

Yes, in the INTERMEZZI (pp. 67–70) I used photos from real estate portals on the internet, which are usually of rather poor quality. I thought about visiting the houses and photographing them on site, but then decided against it. I was less interested in the real experience than in the virtual representation of the properties. (And I found it interesting how images with partly private testimonies are distributed quite publicly).

After the small digitally created collages, I then felt the need to give these spaces, which I only knew as flat images, a spatiality again: So, I printed out the motifs, folded them, staggered them and thus gave the images three-dimensionality again (RAUMANORDNUNGEN pp.62, 63, 65).

However, these spatial structures no longer have much to do with the reality of the houses.

Well, they may have been created based on photographs, but ultimately, they are pure fiction.

A fiction, but one that has become very tangible.

Yes, I wanted to give materiality back to the digital images, which have no materiality, not even that of photographic paper. For example, I printed parts of the image on wood: the image of the wardrobe on plywood (PURPLE CARPET) appears very real in its feel, depending on the angle of view, but turns out to be an illusion at second glance. This game of deception between surface and volume, image and materiality also takes place in the FURNITURE ARRANGEMENT (p.48). I like the play between appearance and reality, illusion and exposure.

Translation: Sylvia Rüttimann